|   |

HOME

BIOGRAPHY

FILMOGRAPHY and

GALLERY

PHOTOS,

AUTOGRAPHS and

PORTRAITS

BEHIND THE SCENE

BANNERS

Comments or suggestions?

E-mail me!

All original content is

© Jean-Paul Rotfeld,

2008 - 2015

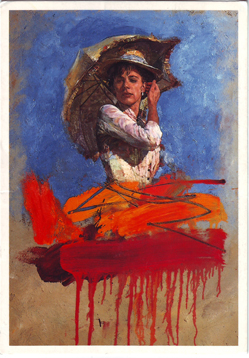

The Bridge:The composer's recollections of making the movieAt the end of the 80's and early 90's, a great editor friend of mine Paul Martin Smith (STAR WARS, BEHIND ENEMY LINES etc.) had built up a relationship working with a lovely director called Syd Macartney making commercials, and Martin kindly introduced us to one another. Syd had been trained as a cinematographer and had a very strong visual style, so for example he'd directed some of the most famous Levi commercials in the 80's that won awards and were shown all over the world. After leaving the National Film School, I think, Syd's first break was as a cinematographer on the movie "PARTY PARTY" with director Terry Winsor (who coincidentally I was also at art school with) and after making his way in commercials Syd directed a UK TV series called Yellowthread Street. By the early 90's Syd wanted to make the final push to movie directing and when we first met, he was making a short called "This way up". Directing a cinema short is one way to be taken seriously if you have the passion and ambition for a movie career, but there is usually little or no production money available, so everyone involved does it for the love of it! Syd was looking for help in producing the score for his short and by then I'd been lucky enough to have already scored several movies. (Renny Harlin's first movie BORN AMERICAN, a UK Film 4 movie called BEASTLY TREATMENT starring Ronald Lacey and a BBC Film called ACROSS THE LAKE starring Anthony Hopkins.) I was therefore in a good position to be of some practical help to Syd with his score for "This way Up" and we met for lunch in Soho (London) to have a chat about it. Unbeknown to me, having just finished shooting the short, he'd already been in discussions with a producer called Lyn Goleby about a movie called "THE BRIDGE". When we met, he sadly explained that his day "had started badly because the finance had just fallen through on a period movie he'd hoped to direct about a painter" .... and it was ..."a dreadful shame because the demise of the promised but complicated finance deal would mean the movie would probably never see the light of day". Syd outlined the movie's premise about an 1880's English impressionist Philip Wilson Steer and the relationship he had with the subject of one of his paintings and how the story was inspired by a real work that Steer painted that hangs in the Tate Gallery. It was intended to have used the beautiful village and coast line around Walberswick in Suffolk on the English East coast as a backdrop to the movie. I thought this sounded like the most heavenly project I could ever imagine and was so sad that it had fallen through for Syd. After our lunch we went over to the cutting room to discuss the music for "This Way Up" which Syd screened for me. As we parted that day I remember mentioning that if one day the period movie about the painter EVER went into production, I'd love to be considered for the score. The following month, the most extraordinary whirlwind of events took place. Just a couple of weeks later, when I was finishing the music for Syd's short film, Lyn Goleby had miraculously found a new source of finance for "THE BRIDGE" and Syd asked if I had anything that I could send him that might persuade he and Lyn (the producer) that I was capable of composing the score for his first movie?! I have vague recollections of trying to persuade Lyn that as this was going to be a score about a painter, my fine art degree in painting at St Martins School of Art would put me in the most ideal position to write their score or some such load of tosh! Although not exactly appropriate for "THE BRIDGE", I think that some of the string arrangements from my score for "ACROSS THE LAKE" contained some music with a lyrical English pastoral feel and as this had been quite a high profile film in the UK, it gave me enough credibility to be offered the job of scoring Syd's movie. Hurrah! The only problem the production might suffer was that although the story was supposedly set at the seaside in the summer, we were quickly running into October and November© however with the luck of some fine weather, this gave the cinematographer David Tattersall literally a golden opportunity to shoot with the most amazing light. As the plot developed, the autumn mist and "season of mists and mellow fruitfulness" worked very appropriately for the stories conclusion. My first work on the film was to compose and produce "source" music for a scene in the movie where the locals are dancing on a village green. ("Source" music refers to music in a film that is part of the fictional setting and is heard by the characters on set, and "score" is the music the composer adds when the film is cut later and just the audience hear). The scene is the village fete and one of the most important scenes in the movie, because it's where the painter - Steer, and his subject - Isobel realize they are falling into a passionate love affair . The story is complicated by the fact that Isobel is married with children and has a husband in London (Reginald played by Anthony Higgins). I researched the possibilities and wrote a piece that would have been typically played by of a small 1880's coastal militia band and recorded an appropriate arrangement with musicians in a recording studio. This recording would be played back on set for musicians to mime to, as a background to the scene being filmed. However, looking forward to the post production, my plan was to later introduce an orchestral score over the top of this source music as the scene develops, that would highlight the warming of the relationship between Steer and Isobel. When the "source" music and the "score" are played alongside one another they clash (in hopefully an interesting way!) to make a really strange powerful atmosphere in order to heighten the drama. So in the final movie the village band would be playing on the green and as the scene slowly changes and night approaches, I slowly start the sound in the score of some high suspended strings playing in a totally different musical style and key, that creates a surreal moment then later when Steer holds Isobel's hand with a provocative gesture, whilst the two characters are surrounded the whole time by Isobel's children, local villagers and the sound of the militia band© the orchestral score then slowly takes over the scene in the final mix and creates the powerful feeling that the two main characters are alone and the score is all the audience hear as if we're reading Steer and Isobel's minds© as they are falling in love, we take the audience away from "real" sound of the village green and the band playing with the f/x sounds of the villagers clapping and laughing, slowly we crossfade until we can just hear the string music of the score, even though they are surrounded by people, they are at this moment the only people in the world. The final score was predominantly arranged for string orchestra augmented by solo violin, sampled ethnic woodwinds together with tuned things that I blew, keyboards and some brass, but as we didn't have a budget for a decent size orchestra sessions, I wrote arrangements that used lots of sampled sound with strings performed by Pete Whitfield - an incredible violinist who played many different violins and viola parts each on several instruments, track by track. It was a long arduous process building up the string textures without a string section but Pete did an amazing job as well of course as playing the solo violin lead parts. I also sampled some "mm" sounds with my own voice that helped to add to the pallette of musical colours for the film. An interesting and major aspect of the production of the film was that the now very well known cinematographer David Tattersall, who was shooting his first movie, eventually volunteered (more like "was volunteered") to draw the artworks and paint the canvas in the movie as we couldn't find anyone good enough to do the job. It was only when push came to shove and nobody was deemed good enough for the job that David "had a go"! He did an utterly amazing job and had the amazingly perfect crafted gift that was needed to represent the painter's hand drawing and painting. However, as the story developed we make it through the whole movie without the need to show the audience the painting of Isobel that Steer is working on for most of his time with her. This was the one painting that David felt he shouldn't paint. In actual fact, I believe it worked in the movie's favour, that the mysterious painting of Isobel, around which Steer had the perfect reason to spend so much time alone in a room with this married woman... the painting that the plot was based around... is never actually seen by the audience! This same painting that Reginald (Anthony Higgins) eventually sees for himself, makes it quite obvious to the husband that Steer's portrayal of his wife is one of a lover and as a consequence of what Reginald sees in the painting, he accuses the painter of having an affair with his wife. When eventually Reginald tricks the painter and buys the painting of Isobel for himself (in a way he's simply paying the painter off), he then burns it on a bonfire representing his control of his wife and termination of their love affair. It is the perfect ending to the film as it explains to the audience that the painter was mistaken in thinking his love for Isobel was nothing more than an infatuation for the sake of the painting, his selfish creative passion for painting was what truly motivated him. Steer wasn't as much in love with Isobel as he was in love with the inspiration that her being the subject of his best painting gave him. For Steer it was all about the painting and the way he saw everything was through his art, in a strange way, perhaps his engaging with life through his painting of it, meant he didn't have to actually engage with anything first hand emotionally for himself. The affair with Isobel was for him nothing more than a means to find and extend himself through his art as a consequence of his finding in her - his favourite subject. Steer's thought that he was creating his best work ever in his painting of Isobel is eventually shown to be not the case. When the husband manages to regain control of the situation (although Isobel doesn't believe that Steer has simply been paid off and is distraught ), we see Steer with great feelings of remorse and sadness at the loss of his subject and lover. However it is through his creativity and art that Steer comes to terms with the emotion of what has happened, some distance away in front him, he sees the husband and wife standing on a bridge as twilight is approaching© they represent and incredible visual enigma... they stand as if frozen in time on "the bridge" slightly apart© they are unable to speak. Without knowing it, they give Steer the opportunity now to turn the emotional journey that he's been on, into his best painting yet, the purpose of his journey has been to paint this strange image of the husband and wife on that bridge. His most powerful work is THE BRIDGE. Musically, the solo violin theme is probably the strongest motif with strange ethnic woodwind and voices represented Steer's obsession for painting. There is also a separate growing theme for the scene when the storm hits and a in addition a kind of "growing of the intensity of their relationship" theme which is the music the audience hear stated in the opening titles and develops when Steer and Isobel are alone (eg. in the score that develops when we loose the band playing at the village fete and we see Steer and Isobel in their own secret world). When Steer and Isobel eventually make love we hear a full blown version of a tiny tune I use for Isobel which becomes at that point a full blown love theme although it is still introduced with the thought that Steer suggests: "I only have one subject now." For him this moment is still all about his obsession for painting, and then after the love scene we cut to beautiful shot of Isobel's twin girls who are running in slow motion on the beach, holding a huge piece of white cloth that they pull in the breeze above their heads, accompanying this image we're musically pointing up the strong emotion of regret. Having finished the movie, Syd and Lyn came up with the fabulous notion that if they could find a real life painter who could now paint the lost and burnt picture of Isobel, in the appropriate impressionist style and use it on the poster in a way that explains the painter's obsession for painting Isobel, it might make an interesting completion of the narrative outside the movie. Indeed if it were possible to see a poster with a recognizable but unfinished image of Saskia Reeves in the impressionist style of the period also much in the manner of the style that the painter was developing in David'd sketches© it would make an intriguing poster. Around the time we started to shoot the movie I'd met an incredible portrait painter called Justin Mortimer who became a good friend, although at the time Justin was just finishing his degree at The Slade Art School. Having shown his work to Syd and Lyn, they immediately asked him to take the commission on and Justin made a wonderful painting that everyone was thrilled with and indeed was used for the poster. However if we'd have found Justin earlier ... perhaps before the movie was shot, David wouldn't have been encouraged to do the amazing job he did with a paint brush and pencil on film. This movie was one of my personal favourites both in terms of the work and the lovely people involved. I'll finish this recollection with a quote that we used in the promotional material for the movie (and I insisted also appeared on the soundtrack album artwork) As well as being a statement I wholeheartedly endorse, it is also very pertinent in relation to the movie: ©I know with certainty that a [person©s] work is nothing but the long journey to recover, through the detours of art, the two or three simple and great images which first gained access to [his or her] heart.©

©Albert Camus Richard G. Mitchel written exclusively for www.anthonyhiggins.narod.ru ©October 2012 |

Back to "THE BRIDGE" page |